Building a tighter analysis and prototyping workflow

Shifting focus from working a goal to engineering the process can create huge productivity gains.

Human powered flight has historically been a particularly hard engineering nut to crack. An engineering challenge set by Brittish industrialist Henry Kremer in 1959 went unmet for 18 years — fly an entirely human powered aircraft in a figure eight pattern around two poles a half-mile apart. For almost 2 decades, the £50,000 prize remained out of reach, as dozens of teams failed to achieve the feat. Finally, a man named Paul MacCready and his team were able to meet the challenge within just six months of attempting it. In 1977, the MacCready Gossamer Condor became the first human powered aircraft capable of controlled and sustained flight. Just two years later, MacCready and team won the second Kremer prize of £100,000 when the Gossamer Albatross flew from England to France. What was so different about this team? What enabled them to find success where others could not?

a change in focus

The secret to their success was to recognize that the problem that needed to be solved was not that of engineering human powered flight, but that the prototyping process for designing the aircraft was inefficient. MacCready recognized that the prototype-test-redesign loop was far too inefficient. While other teams were taking much longer – a year or more – to build their prototype aircraft, the MacCready team focused on finding ways to build, modify, and rebuild the aircraft quickly. Ultimately, the MacCready team was able to turn out a new prototype sometimes twice a day, while other teams took much, much longer to build their prototypes. It was this simple change in focus – from engineering the aircraft, to engineering the process – that enabled the team to vastly improve their prototyping efficiency, and ultimately, their engineering velocity.

We often see a similar pattern in our own work. Perhaps it’s human nature to attack a problem or pursue a goal directly – almost blindly. We all want to feel that we’re making progress toward a goal; and attacking a problem head-on can often make us feel productive. This can lead us into work patterns that are less than efficient, perhaps without our awareness. So it’s often beneficial to step out of the heads-down work mode to examine how we’re solving problems.

Often, bringing a new product to market involves research and development encompassing an iterative workflow. Whether the product is hardware, software, pharmaceutical or something else, there’s a build/test/analyze/modify loop that plays a huge roll in how fast we’re able to bring the product to market, and at what cost. Looking for ways to eliminate inefficiencies in that workflow loop can lead to huge gains in development velocity and cost, and a shorter path to success. It can be the difference between project success and failure; going to market and being beat to market; finishing in budget and blowing the budget. One thing that I like about the software world is that it offers us lots of opportunities to address such inefficiencies.

hacking the workflow

Not long ago, I worked with a client (let’s call them X Co) who is using computational analysis to design, test, and build their hardware product (XWare). In the process of designing and testing XWare, they had to endure a very cumbersome workflow loop involving quite a bit of manual work and a lot of repetition. This workflow consumed an enormous amount of time, physical and mental energy, and caused X Co to struggle to meet milestones.

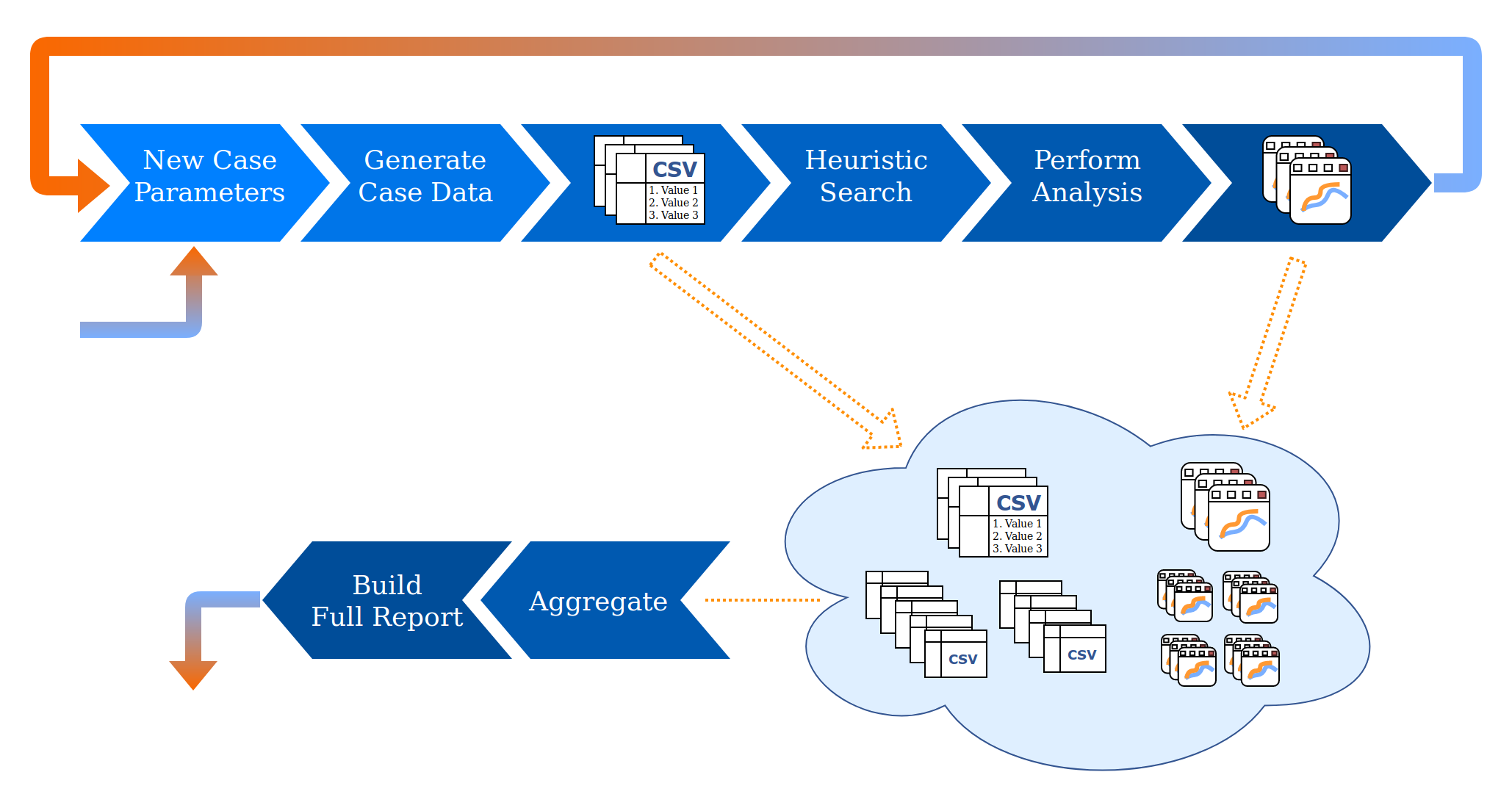

The X Co workflow involved doing parametric studies to search for heuristic success indicators within a data set produced using computational flow analysis algorithms. That’s a bit of a long-winded way of saying they need to repeatedly and iteratively generate data in order to search through and analyze the data, looking for indicators of a successful design. At a high level, the process looks like this:

- Generate computational flow analysis data for a specific combination of XWare physical and environmental parameters. Each specific combination of parameters, known as a case, represents specific features of XWare and the environment it operates in. The computational flow algorithms analyze these features in order to generate specific performance data for a version of XWare.

- Manually search the data set associated with the case for heuristic success indicators in order to accept or eliminate the solution represented by that case.

- Manually perform analysis and produce and annotate graphs and other media for a successful case, or reject the unsuccessful case.

- Repeat the above steps for every combination of parameters, in order to analyze every possible case in the study. This produces a large corpus of data and analysis artifacts which need to be collected, sorted, aggregated, and distilled into a final analysis.

- Finally, aggregate analysis and results from each successful case in order to produce a full parametric study.

The process of producing the computational flow data involved hand modifying a parameter and manually producing a data set for a new case. This produced a large, relatively disorganized data set representing a single case, which needed to be stored in an organized fashion for analysis. In addition, a practitioner would be required to wait quite some time while the data was being generated for the case. After data generation completed, he could begin to manually search the data set for heuristic success indicators, using a spreadsheet to look at a sea of numbers from raw CSV data. After this tedious process, the task of building and hand annotating graphs and other analysis media would begin. Finally, all of this work needed to be repeated for every combination of parameters in the search space.

Having to repeat the entire cumbersome manual process for every combination of parameters is a Real Problem. To see why, consider that the number of cases to be analyzed grows multiplicatively with the number of possible values for each parameter in the study. So adding even a single new parameter value to the search space could greatly expand the size of the search space, leading to an enormous amount of new work.

redefine the problem from “how can we build a great XWare?” to “how can we build a great XWare design process?”

Working with X Co, we were able to understand their workflow, and ultimately redefine the problem from “how can we build a great XWare?” to “how can we build a great XWare design process?”. We focused on building an efficient XWare design process that also empowers us to continuously improve the process itself. We chose technologies and made design decisions that we believed would lead to a system that is capable of growing and evolving. We started by defining three goals for the project:

- eliminate the cumbersome workflow loop X Co found themselves working in

- simplify and refine the process of doing analysis on the data

- build a system that enables continuous process evolution, to enable growth that keeps pace with business needs

building for abstraction

Our first task was to build a system that automates data generation, combining all data from all cases into a single search space. The new system allows X Co to generate all of the data in a search space by defining parameter values up front and just letting it run. This abstraction greatly compresses the amount of time required to generate test data, and frees up valuable brain real-estate to focus on analysis.

We chose to employ Apache Solr as our data store. No doubt, some of you are asking, “why the hell would you use a search engine as a database for computational data?”. Well, when you think about it, Solr is actually a database — but with a more powerful query language than a typical SQL database. It’s fast, scalable, easy to deploy and configure, and capable of handling a wide range of use cases. Most of all, the query language lends itself well to teasing insights out of data. It’s often impossible to know what you’ll want to ask of your data in the future. So it’s important to choose a data store and query paradigm that can evolve with your needs, as they arise. We often reach for Solr in our data architecture projects.

We chose to use Venturi to aggregate and normalize the data, and move it from flat files to Solr as it’s generated. Venturi is a framework we built and use internally with our clients to build scalable data processing (ETL) engines. It employs a pluggable architecture and a custom transformation description language that makes it easy to describe a transformation pipeline, and route data from a data source to a data sink. Venturi also greatly simplifies the process of updating and iterating on the transformation pipeline to address changing data or business requirements. And since it’s scalable out of the box, it can grow with the size of the data set. So our use of Venturi builds nicely on our goal of enabling continuous process evolution.

refining the analysis

Having addressed data generation, we turned to data retrieval and analysis, aiming to simplify and automate heuristic search where it made sense. There were a number of concerns for this part of the project, including the size of the data set (and the high probability it will continue to grow), convenient remote access, and support for multiple users. So a web based analysis portal made sense for this project. In addition to supporting scalability and enabling portability, it allows for fast deployments of fixes and enhancements.

Working with X Co, we defined a standard set of heuristic visualizations they use to analyze each case. The portal was designed to generate these visualizations automatically for the full study. Pulling all of the data for a study into a single search space enables analysis at a level previously unavailable to X Co. Starting with the standard visualizations, users can use filters to limit parameter values, eliminating irrelevant cases and updating their visualizations in real-time. Using the new portal, it’s easy to quickly visualize success cases, determine successful parametric ranges, and compare multiple cases with one another. The portal also makes it easy to visualize and eliminate failure cases from the study, so that focus can remain on the success cases. Finally, the portal makes it easy to export analysis graphics along with the underlying data, in order to build the full parametric study.

summing up

By isolating repetition and encapsulating it into a software abstraction, X Co realized a surprisingly large gain in development velocity. And they have the ability to continue improving their development process over time, thanks to a software system designed from the ground up to be malleable. With continued diligence, their development process will grow and evolve with them. Most importantly, their gains will continue to compound, as they have more time and mental real-estate to focus on the other aspects of their path to success.

The inefficient iterative workflow loop we saw with X Co is surprisingly common. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to step out of the work to examine how it can be done more efficiently. But doing just that can be an important part of finding success – and it can lead to big, relatively cheap gains in development velocity. Any time we observe ourselves doing repetitive work, it could be regarded as the canary in the coal mine, and an opportunity to improve our approach. Can you identify the ways that you’re working inefficiently? Next time you do, think about how can you improve your approach to your work and increase your own velocity.